Alumni Update: Manisha Anantharaman

Manisha Anantharaman, a 2007 Inlaks Scholar,

is currently Assistant Professor, Sociology of the Environment at Sciences Po.

Her book ‘Recycling Class: The Contradictions of Inclusion in Urban Sustainability’ has been published recently by MIT Press.

Congratulations on the release of your book. Can you tell us a little bit about it?

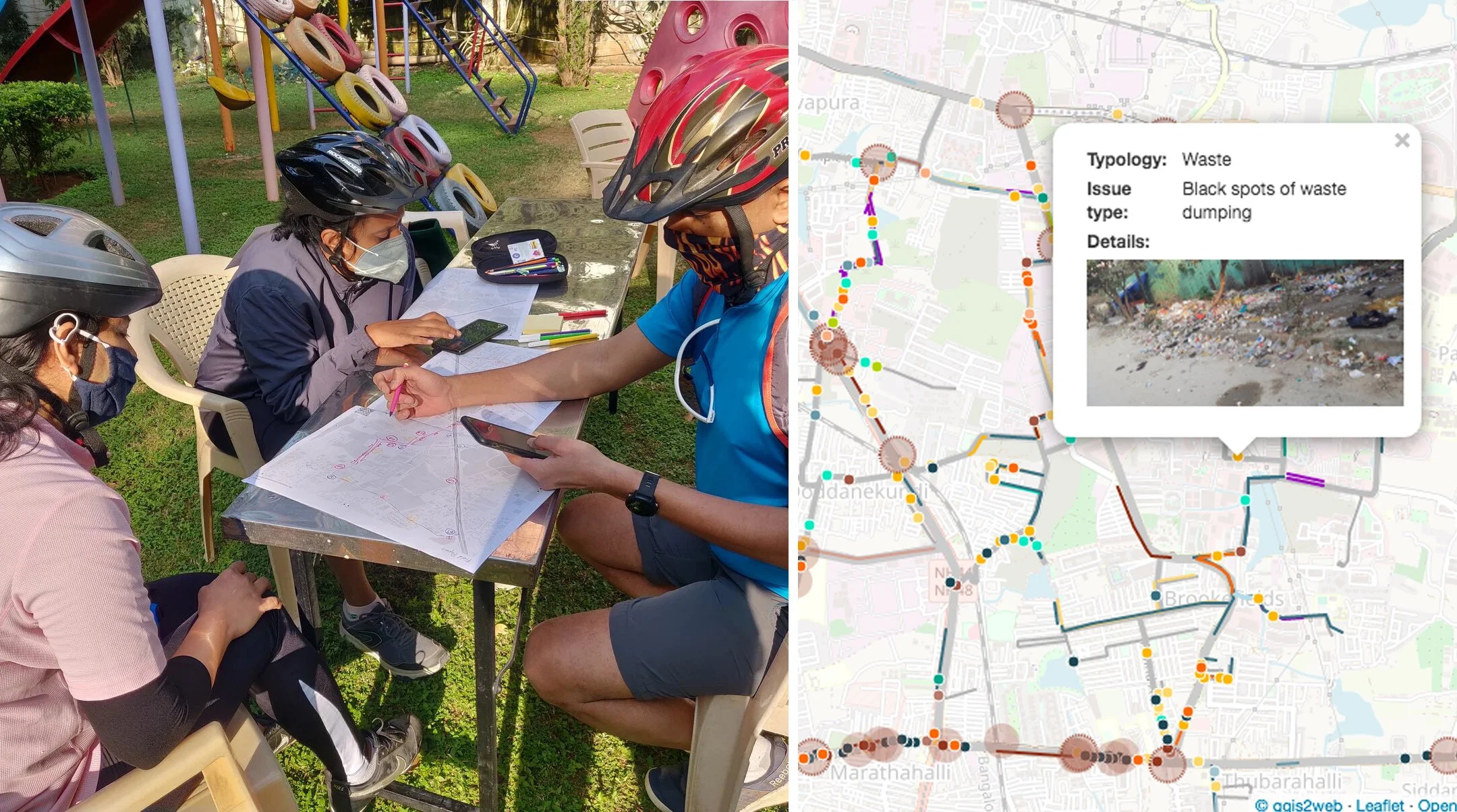

Recycling Class is the product of a decade-long, community-engaged and ethnographic study analyzing the class, caste and gender politics of the environmental mobilizations that articulate around unmanaged waste or garbage in Bengaluru, India.

In the past three decades, Indian cities have experienced a very significant increase in what is sometimes termed “consumerism” and with it come local and global environmental impacts. Alongside unequal growth and development, Bengaluru, like many other Asian cities, is also experiencing local environmental externalities of growth such as increasing air pollution, urban heat islands and water scarcity. Perhaps the most visible signs of this growing environmental toll are to do with the country’s enduring problems with unmanaged waste or garbage.

In the book, I trace the flows of both waste materials and sustainability discourses and link an examination of middle-class (sustainable) consumption with the (environmental) labor of the working poor to offer a relational analysis of urban sustainability politics and practice. I studied middle class groups, composed mostly of women, who are responding to the garbage crisis by taking matters into their own hands and pursuing zero waste behaviors and policies at the neighborhood and city level by promoting reduce, reuse, recycling, and composting. I also look at the garbage crisis and attempts to enact a zero-waste transition from the perspective of organizations representing waste pickers, who are individuals and communities who make a living by gleaning valuable materials from the roadside and municipal dumps, and I examine when, how and why the agendas of middle-class movement and waste pickers converge.

I demonstrate that the very presence of waste pickers in what I term communal sustainability, which are these local, place-based zero-waste movements that counter the technocratic and managerial approach to managing garbage, challenges the existing discourse and forms of environmentalism, forcing the middle classes and the state to consider livelihood, occupational health, and social welfare as crucial elements of sustainability transitions. These co-produced “DIY infrastructures” that connect middle class environmental groups and waste pickers serve as sites of citizenship and political negotiation. Yet, I also find that while waste-picker organizations have used the waste and urban sustainability agenda to create new avenues for economic inclusion and political negotiation, the same agenda also reproduces unequal distributions of risk and responsibility. To move forward, privileged environmentalists, scholars, and activists must listen to waste pickers and prioritize social reform and reparation over aesthetics or efficiency.

What are the key insights the book offers?

The book is a critique of a sustainability agenda that tends to ignore or sidelines issues of social justice. Often, in the popular narrative of what causes plastic pollution, the problem of garbage is often reduced to littering, poor behavior, or poor management; or workers are blamed. Yet it is much more complicated than that.

Indeed, blaming consumers for bad behavior or poor waste management infrastructures is a key tactic utilized by large corporations and big polluters to divert attention away from plastic over-production.[1] Also central to this strategy is the devaluation and the scapegoating of informal waste workers who have long been blamed for urban dysfunction and global environmental crises. While this strategy relies on calculative tactics such as underplaying the role of waste imports and exports and flattening global flows and intranational differences by citing per-capita, nation-level statistics, it also relies on modes environmental and economic imaginaries that devalue informal work and workers, who across the world tend to be disproportionately women and from ethno-racial and religiously marginalized communities. Urban policy also promotes legalistic formalization projects that privatize informal economies and dispossess workers.

Yet, the tide might be turning. Waste pickers, informal recyclers, and their representatives are fighting back, using local and global environmental summits as critical terrain to reassert their right to the city and global ecologies. Their efforts are gaining momentum: The 5th UNEA declaration in 2022 to develop a global plastics treaty references the importance of learning from informal settings and waste pickers have been called “any city’s key ally.” However, in my book I argue that if these inclusion efforts are not to reproduce existing caste-based, racialized and gendered patterns of exploitation and dispossession, they must begin with an acknowledgement of past harms and understand their gendered and racialized dynamics. This acknowledgement cannot be just in the form of words but in the form of explicit procedural measures to prioritize the voices of workers in policymaking, as well as social reform through an anti-caste and anti-racist ethic, and through reparation of resources to these communities to address distributional inequities.

[1] Mah, Alice. 2022. Plastic Unlimited: How Corporations Are Fuelling the Ecological Crisis and What We Can Do About It. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

What has drawn you to the study of garbage politics over the last decade?

I started my academic career as a biologist and ecologist. I was drawn to ecology because, like many people growing up in India in the 90s and 2000s, I lived amidst rising air pollution, heat, and water stress. I developed an interest in plant and animal life almost because these forms of more-than-human life seemed to be disappearing quickly from the city. However, it was only during my Masters at Oxford and later my PhD at UC Berkeley that I fully comprehended that environmental problems are social problems.

Relatedly, encounters with garbage, and mosquito-borne diseases, were a feature of my urban existence. As a child, I contracted malaria six times. Each time I became emaciated. The mosquitoes that grew aplenty in the waste choked Cooum River next to my house loved me. My mother was asthmatic and allergic to every mosquito-killing chemical out there. My unfortunate nickname in school was Malaria. This formative experience was my first lesson in political ecology—there are no privatized, consumer-centric solutions to shared environmental problems.

Thinking about garbage politics also makes me hopeful. By looking at this case study in Bengaluru and zooming out from it, I hope to show the reader that our systems of production and consumption do not work for most people in the world. Whether it is waste pickers materially deprived of basic dignity and forced to sort through refuse to make life, or the middle-class mother in Bengaluru worried about her child’s fourth bout of malaria, waste reveals a broken economic system. Recognizing the interlinked nature of ecological violence and human suffering across diverse positionalities can help us see our mutual vulnerability. Waste flows form the material bonds of our mutual vulnerability.

What have been some of the challenges and learnings you’ve had over the course of writing and publishing this?

I wanted to write a book because I did not feel I could do justice to this complex story in any other form, and also because I felt the need to bring in a personal dimension to explain who I am in relation to this project. Writing a book gave me the space to interweave personal reflection and autoethnographic vignettes into the narrative. This was also probably the hardest part of the process!

The simple fact of the matter is, my habitus, the way in which I grew up in Indian cities, the privileges I was afforded were built upon casteism. Yet, casteism was always presented to me, in my textbooks as well as in my immediate social circles, as something of the past, which I now know is not accurate. Throughout the book, I reflect on my own positionality, the ways in which my biases and prejudices have been challenged by my engagement with diverse actors, and my struggles to reconcile what I witnessed with what I thought I knew.

Quite simply, there can be no just sustainability as long as environmental initiatives ignore, condone, or reproduce casteism. Scholarship on Indian cities and environmentalism is finally beginning to include caste within its analytic, thanks to the efforts of Dalit scholars and activists. Rejecting casteism involves recognizing the reality that salubrious environments and economic gains for dominant-caste, middle-class, and elite groups in India has always come at the cost of oppressed castes. Thinking about casteism as an expression and form of racialized oppression connects the struggles of Bengaluru’s waste pickers to the struggles of racialized and othered communities all over the world.