Alumni Update: Ankit Bhargava

Ankit Bhargava is a 2011 scholar who pursued at an MSc in Urbanism at the Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), Netherlands. He is an urban planner who co-runs a Bengaluru based do-tank called Sensing Local.

In this blog he looks back at some of his experiences while sharing insights on the current limitations faced by urban planners and how he believes they can be overcome.

Discovering the new role for urban planning and planners

I am an architect turned urban planner and I now co-run a do-tank called Sensing Local, based out of Bengaluru. We focus on tackling environmental issues in urban and rur-urban contexts. 2021 marked just over 10 years of my engagement in the profession. Looking back, the ride has been a roller coaster of successes, pitfalls, and radical pivots. This article reflects out loud on some of the experiences and insights so far.

My foray into urban planning started fortuitously as an architect-researcher in a project to create an urban management plan for the Fort area in Mumbai. The making of the neighbourhood maps, and unpacking the layers of the urban fabric opened up new ways of looking at an adopted city. It revealed clues for sense-making of Mumbai’s apparent chaos, like secrets that only reveal themselves after decades of living in some place.

Returning to India as an urban planner, I was a researcher in a high-level government project to restructure the municipal governance and operations of Bengaluru. The idea was to explore how the Bengaluru municipality that serves over 10 million people could be divided into smaller municipalities on the lines of other global metropolises. The intention being to reduce the scale of the unit of governance and therefore optimise how to tackle the complex urban issues. This was followed by the Neighbourhood Improvement Partnership (NIP), a unique project in 2015 conceived during the time when the national focus was shifting to cities through the introduction of smart city projects. It was a city-wide competition designed to provide 1 crore of CSR funds for innovative and scalable community-based neighbourhood projects to improve livability. It was imagined as a new model to build capacity at the local level putting users at the heart of solving their civic issues.

At Sensing Local, over the last 5 years, we have been engaging in projects across the thematics of waste management, water management, air pollution and way-finding signage, urban poverty, and now most recently sustainable transport. Some of the key projects have included -

Creating a rejuvenation plan for Varthur lake, the second largest lake in Bengaluru, that enabled the allocation of 500 crores of public funds towards implementation, in tandem with another lake upstream.

Supporting the development of the GIS database for Bengaluru’s solid waste management department, to enable data-driven strategy development and plan making

Introducing multi-stakeholder participation in several public projects to augment inputs for issue mapping, planning and even solutioning such as the audit of Bengaluru’s dry waste collection center

Creating place-making signage for one of the city's largest and oldest (~140 years) parks, that offered a way to see the cherished public space through the historical, cultural, ecological and recreation lens, gathering over 35 layers of unique data point

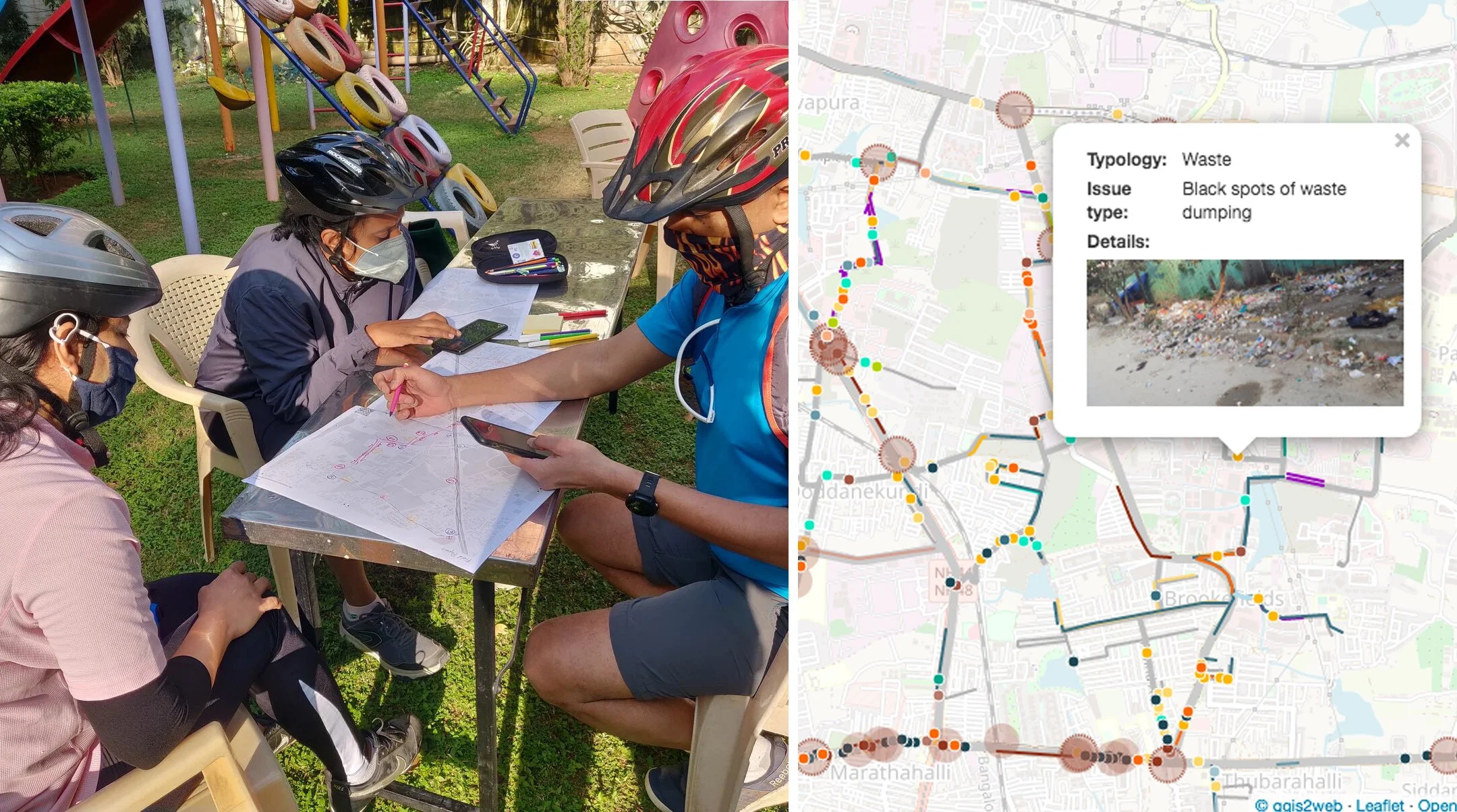

Neighbourhood-based initiatives for designing and piloting infrastructure for cycling, walking, and improving public space

Development of a system for decentralized covid management as part of a consortium of civic organizations

Signage at Cubbon park, Bengaluru. (https://www.sensinglocal.in/post/integrated-wayfinding-system-for-cubbon-park)

While these projects have been exciting, tracing their journey also reveals what it means to operate in this nascent sector. NIP failed because of lack of interest by city officials, despite it once being wooed to be scaled across the country. It took over 2 years to develop the rejuvenation plan for Varthur lake and there has been no on-ground change in the last 3 years despite budgets being available. Years of working with the solid waste department, helping build capacity through training programs and manuals, developing city strategies is constantly threatened to be undone because of the politician-contractor nexus that profits off the sector that commands almost 20-30% of the city’s ~ 7000 - 8,000 Crore budget.

Website for COVID information and enabling decentralized management in Bengaluru

While global attention has gotten Indian cities to start thinking of cycling, the spending for cycling infrastructure in a city like Bengaluru is likely less than 0.1% of the city’s road development budget. The signage project in Cubbon park now is also home to ant colonies and the component of the signage proposed to serve the visually impaired never found funding. The platforms and plans for decentralized covid management built pro bono over several months were dismantled a week after its launch by the then city commissioner in mid-July 2020. It was learned later than internally in the government it was believed covid was ending by the end of July.

These problems may seem singular, small, and perhaps unsurprising. However, the trend makes you question if we are ever going to break through the status quo. The quality of public life across the Indian cities is deteriorating and the inherent asymmetries and inequalities are taking a heavy toll on individual people and families in terms of personal health, expenditure on housing, travel, mental health, opportunities for recreation, etc.

In terms of effort, we seem to be going in circles. The same issues are brought up year upon year in city after city. Government agencies are constantly firefighting yesterday’s concerns and there seems to be little to no appetite to commit to long-term decision making. One of the key reasons for this is the shocking lack of capacity to deal with the scale of urban issues. Tackling social housing, urban poverty, or climate change seems impossible in the near future.

The public as users continue to be seen as the ‘problem’ whether it is in discussion why infrastructure and urban services are falling short or why participation is unnecessary. Plurality and diversity are seen as a hurdle, rather than the underlying condition to respond to. In all this, what seems to be missing most is the courage and commitment to moving towards an inspired future that has room for everyone, be it young, old, poor, disabled, migrants and long-term residents. The pathway for change in this decade and this generation is conveniently unclear.

However, what’s been interesting thus far is that this kind of work for most part has been significantly different from the typical spatial and master plans that urban planners are associated with. There are more avenues than ever before for how urban planners can engage. This is good. It's only fair to end this article on a positive note. So, in all the twists and turns, there are certain roles and ways of working that have stood the test of time that are worth sharing.

Urban planners need to -

Be the unbiased experts in any room, working horizontally to bridge all stakeholders

Curate and create evidence in the form of scientific information and on-ground experiences to compensate for lack of public data

Provide the systems view of complex problems, so each stakeholder can find their role in it

Design process-based frameworks that offer pathways for working to break paralysis due to high uncertainty and ambiguity.

Lead with empathy and inspiration

Be tech-enabled, harnessing the multitude of open source technologies acting as end users and creators

Lastly, mainstreaming planning has also meant strengthening governance and democratic systems. Working in the planning sector has been a revelation in terms of getting a sense of who we are as a society, how we treat each other, why we have the stark inequalities we do and how class, caste, religious and ideological differences play out. Importantly, it has not just been a place of observation but also intervention. Processes of planning can radically augment participation of marginalized voices by designing for inclusion from the get-go, and draw attention to underrepresented issues that need critical action.

In the next decade, we hope to further this work anchored between enabling civic participation - supporting creation of new open and representative urban data - inclusive planning and - using technology to simplify and modularize efforts for scale.

Cover Image: Issue mapping and planning for neighbourhood cycle lanes with local citizens in Doddanekundi, Bengaluru. (https://www.suma-doddanekundi.in/)