Grantee Update: N.S. Abhilasha

N.S. Abhilasha is a Ph.D. scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati. Her area of interest lies in the troubled histories of epidemics in Assam (1860-1950).

This short essay explores how a major scientific discovery elicited divergent responses in different plantation contexts of the British Empire in the 1920s and 1930s. It is a snippet from the archival research that she conducted in the United Kingdom as part of her doctoral work with the support of the Inlaks Research and Travel Grant, 2021.

Malaria Research and Plantation Enterprises

Ronald Ross (1857-1932), a British medical doctor, discovered in 1897 that the bite of an infected female mosquito spreads malaria. He received the Nobel Prize for Physiology for his discovery in 1902. Ross’ elucidation came at a time when diseases kept the average life expectancy below thirty years in many British colonies. While quinine could be used to treat malaria, it was neither a full-proof solution nor could it prevent people from being infected. In the twentieth century, Ross devoted considerable time to promote methods that could control mosquito breeding. ‘Anti-malarial operations’ such as spreading oil or Paris Green over water sources, and draining stagnant water could prevent the proliferation of the malarial larvae. Ross saw such measures to be especially relevant for plantation enterprises where immigrant workers not immune to malaria had high chances of getting infected. The rubber plantations of the Federated Malay State and the tea plantations of British India were potential sites for these experiments. A comparison between the two revealed how different plantation enterprises forged divergent relations with medical science to deal with diseases. These divergences help us understand the constant anxieties of seemingly ‘universal’ medical science.

In March 1927, The Evening News, a British newspaper, reported that Ronald Ross was upset with the tea planters of Assam, a province in British India’s northeastern frontier. He was disappointed by the lack of coordination among them in taking up ‘anti-malarial works.’ The planters in Assam, Ross complained, spent only on tea garden hospitals rather than on the methods that could reduce mosquito breeding. Ross was reported saying, “For what is the use of science making discoveries if they are not acted upon?” On the contrary, he was happy with the efforts put in by the rubber planters in Malaya. Mortality due to malaria had decreased considerably in the Malaya rubber plantations since the 1900s. In Assam’s tea plantations, fifty percent of the workers, on average, were infected with malaria in the 1920s. One in every ten deaths was caused due to malaria.

There were others, besides Ross, who were concerned about the inaction of Assam’s tea planters. In 1938, in an article in The Assam Review and Tea News, a magazine that discussed issues of tea plantations and planters’ culture, a British colonial administrator retold the success of ‘anti-malaria works’ in the Malay State. This article came a century after the tea plantation enterprise had taken its first steps in Assam. While the administrator expressed disappointment with the way planters adopted scientific discoveries, he seemed hopeful that the ‘successful practices’ of one plantation could be emulated in another. He described malaria control as an economic proposition for the plantations—the cost of anti-malarial measures was lesser than the cost of sickness, mortality, and loss of the productivity of labourers due to malaria. While the Malay State, the article added, had understood the economic proposition and acted on it, the plantations in British India had not.

Historical scholarship on the tea plantations of British India has highlighted how planters paid no heed to science when their profits were threatened. The same does not appear to hold true when we look at archival materials that cover a much wider geographical scale. We saw through non-official printed sources—a newspaper and a magazine of the twentieth century—how the plantations in the Malay State and British India despite facing a similar challenge, responded differently to Ross’ proposition of malaria control. The negotiations between medical research and plantation enterprises varied based on the context. The variations prompt inquiries into the fluid nature of science that could be shaped by regional specificities. They also hint at divergent experiences of plantations with diseases and deaths and the worry it caused the Empire and the common people. These are issues that I will explore further in my research.

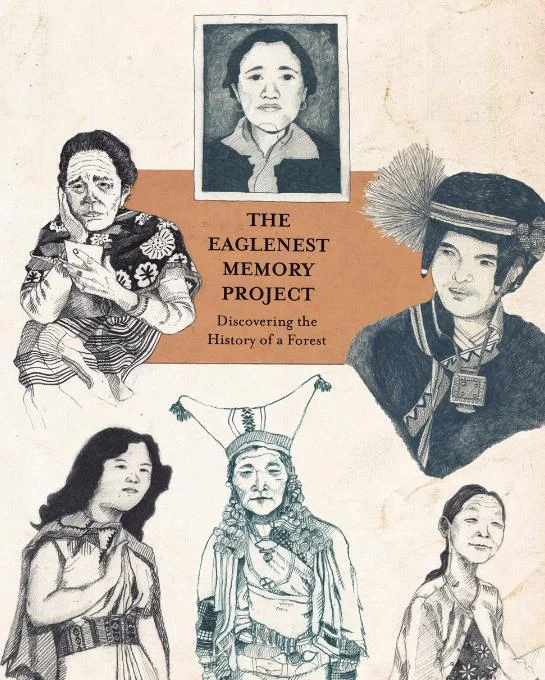

Top Image: Cover Page of The Assam Review and Tea News, Volume XIX, No. IV, June 1938 (Photo taken at the Centre of South Asian Studies, Cambridge University)