Delfina Foundation 2021: Priyanka D’Souza

Priyanka D’Souza attended the Delfina Foundation Residency, London in 2021 with the support of the Foundation.

In December 2021 she presented her paper entitled The Dragon in Medieval Islamic Iconography—(like your life, all tied up in knots!) at Cambridge University, for the conference, ‘The Multimedia Craft of Wonder: Forming and Performing Marvels in Medieval and Early Modern Worlds, 1200-1600.’

This paper examines knots semiotically and materially as “points of density (Bernau 2021)” and discursive devices of object mediated communication in the medieval Islamic world i.e. Asia minor to Iran between the 11th and 13th centuries, particularly as they occur on bodies of dragons/serpents/snakes. With a focus on their magical and talismanic properties, it looks at knotted-reptile iconography on portable objects, architectural reliefs, and in illustrated manuscripts but also addresses the conceptualizations of knots in religious texts, performative ritual and sorcery, and in practical and ornamental usage to show how knots as “meaning-making locations”, uniquely position the human between the material world and the supernatural.

In this week’s blog post she shares with us an extract of her presentation.

“If someone has tied a knot with an incantation in it, he has done sorcery” (man ʿaqada ʿuqdatan fī-hā ruqyatun fa-qad saḥara): ʿAbd al-Razzāq, al-Muṣannaf, 11:17

Figure 1. Al-Jazari’s design for the door of the Artuqid Palace at Diyarabakir, Jazira; 1206 CE; ‘The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.’ Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, A. 3472; 24.5 × 33 cm.

This strapwork interlacing pattern on this illustration of a proposed door (fig. 1) is called girihbandi or the girih in Persian—‘girih’ meaning ‘knot’ and ‘bandi’ meaning ‘tying’—the girih being the nodal element at which the straight lines meet. This purely geometric vocabulary emerged as a prominent mode of design in the medieval Islamic world with the growing constrictions placed on figural representation coinciding with the rise of orthodox Sunni Islam under the Seljuks from the 11th to 13th C. The girih was a highly codified system of a limited vocabulary of star-and-polygon compositions based on invisible gridlines.

In its three-dimensional, spatial iterations on architectural surfaces, the girih, also known as ‘uqood’, ‘uqad’, ‘aqd’ meaning ‘knot’ in Arabic, was also associated with a mathematically ordered, harmonic cosmology and its possible infinity of pattern had theological implications. However, practical geometry was also very important and was used to train artisans and architects and the branch that was used for the construction and facades of buildings was known as ‘ilm al-uqud al-abniya’ or the ‘science of knots of buildings’ where ‘uqud’ or knot could also be the vault or arch that functions as a gathering of architectural planes.

Figure 2. Diagrams from Sulayman al-Rawandi’s Rabat al-sudur wa ayat alsurur showing the derivation of cursive Arabic letters from the module of the circle and its diameter subdivided by dots; 1238; Ink on paper; Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Persan 438. Image from muslimmatters.org

Figure 3.Illuminated frontispiece from the Ibn al-Bawwab Qu’ran; Baghdad, 1000-1001; Colored inks and gold on paper. Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, MS K.16, f. 7v.

According to Gülru Necipoğlu, the girih is likely to have originated in late Abbasid Baghdad where the aesthetically related field of calligraphy also became codified based on the principles of geometric design (fig 2). Both the girih and the new Quranic scripts were governed by invisible proportions using circumference and radius which suggests that they were both developed in the same milieu. She gives an example of them both juxtaposed for the first time on the frontispiece of this 11th C Quran manuscript, now at the Chester Beatty Library (1995, 104) (fig. 3). But calligraphy and mathematical geometry have a much longer association as seen on architectural examples of the geometric Kufic script that function as ornamentation. In plaited or interlaced Kufic, popular between the 11th and 13th C, the bands of some of the elongated letters are intertwined with each other while other letters are stretched to form plaited knots in another register as seen in this 13th C Seljuk tomb façade of the Keykavus Hospital in Turkey (fig. 4). Or perhaps these 13th and 14th C tiles from Iran and Samarkand respectively (fig. 5, 6). The meanings of the words and names that these letters spell are inextricably ‘knotted’ with their ornamental geometric form. This returns us to our original deliberation of knots as complex meaning-making locations.

Figure 4. Detail of entrance to mausoleum, Izzeddin Keykavus Darüssifasi hospital; Sivas, Anatolia; 1217-20 CE. Image from alamy.com

Figure 5. Lustre-painted tile with inscriptions including two whose verticals are connected; Iran; 1250-1350; 58 x 51cm; London, V&A Collection, acc no. C.1976-1910.

Solomon Gandz theorises on material knots as mnemonic and mathematical devices such as rosaries or in abaci for counting, and keep accounts (1930). He suggests that the word ‘abacus’ comes from the Hebrew word, ‘abaq’ meaning ‘knot’ or ‘turn’ and in Arabic, the term ‘uqud’ was used for the knots in tens and hundreds. Knots as memory aids and primitive devices of record are important to understand their linguistic and semantic properties for their ability to make tangible a memory by calling upon a recollection. Gandz opines that knotted cords were the first memory registers that required mechanical memory to bind them which developed into the memory-machine of modern writing resulting in certain alphabets imitating knot forms. While this might be a bit too easy an assumption as most cursive scripts would involve looping and knotting of the line as it moves through time and space to form meaning, it is useful to think of knots as discursive densities that exist in the liminal space between a material existence of human affordance and abstract ideation.

Figure 6.Carved earthenware tile with turquoise-glazed calligraphy, Uzbekistan, 1380-1420 CE; 34 x 26cm; London, V&A Collection, acc no. 1286-1893.

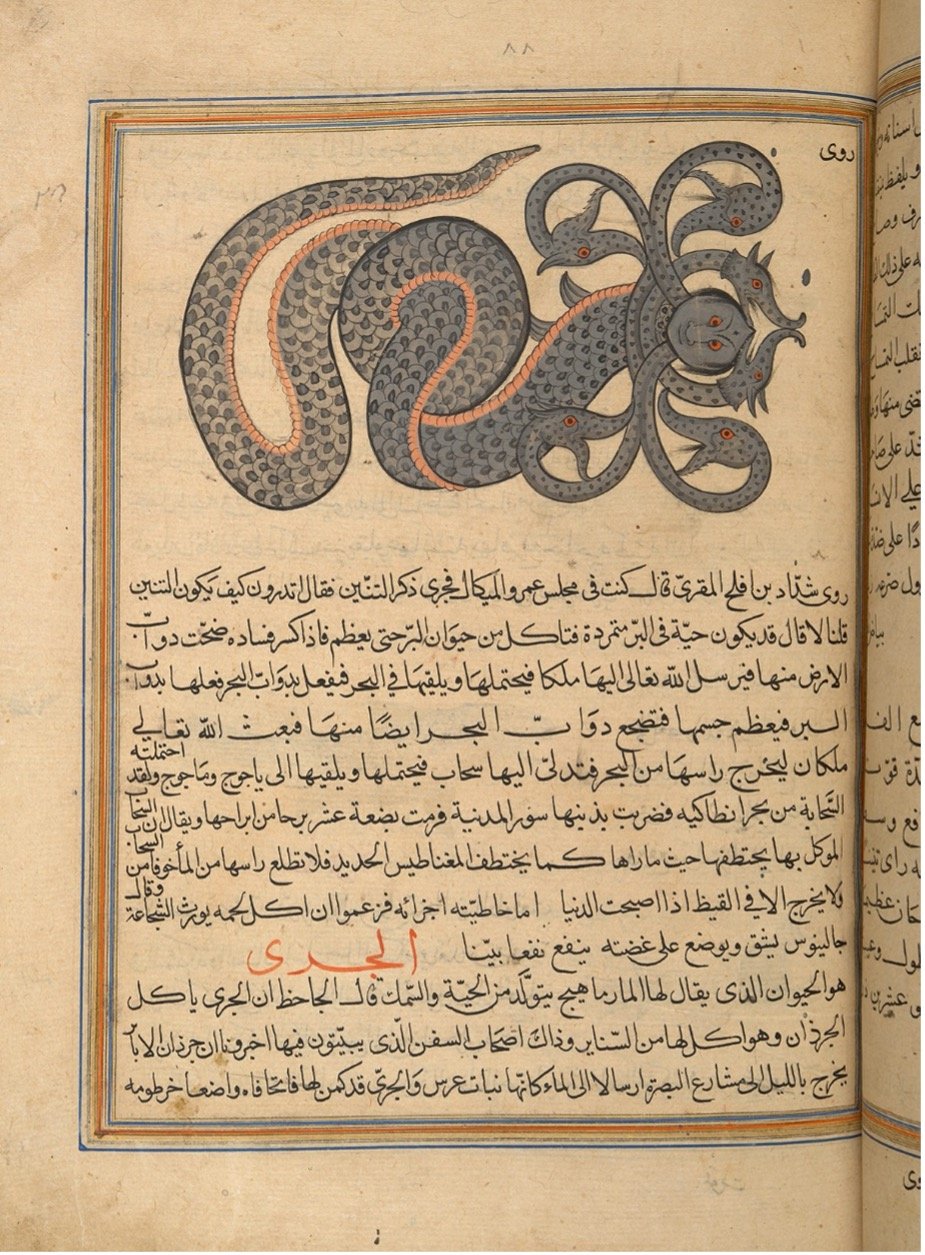

And so, when we look at the painting of this snake (fig. 7) or this sea-serpent monster called al-Tannin, (fig. 8, 9) from al-Qazwini’s 13th C Arabic cosmography, ‘Aja'ib al-Makhluqat wa Ghara'ib al-Mawjudat or ‘The Wonders of Creatures and the Marvels of Creation’, we can better understand the presence of these seemingly random knots in the illustrations of these serpent-bodies. Their corresponding text, interestingly, makes no mention of knots and the knots thus exist solely in the visual, despite these illustrations being created over the following few centuries. The ‘ajai’b’, literally meaning wondrous/marvelous, was a genre of literature which remained popular in Islamic culture even after the medieval period. While many scholars variously interpret these illustrated knotted serpents as either having connections to the astrological eclipse dragon or being just an ornamental motif from architectural reliefs (Carboni 2015, 67-70), we know that knots are more than their purely symbolic meanings or iconographical properties.

Figure 7. Snake (hayya), illustrated in the ‘London Qazwini’, Aja'ib al-Makhluqat wa Ghara'ib al-Mawjudat (The Wonders of Creatures and the Marvels of Creation); 14th C, Mosul; 103×168 mm; London, British Library fol. 128r. Image from Stefano Carboni, The 'Wonders of Creation': a Study of the Ilkhanid 'London Qazwini', Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2015; fig. 310.

Figure 8. The Dragon Fish, al-Tannīn, from the Wonders of Creation of Qazwini; 15th C, Iraq or Eastern Turkey; 32.7 x 22.4 cm; Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. acc no. F1954.70

Knots are incredibly human things, made by human hands and yet slip from our grasp. The artists here have really taken into account the thickness, elasticity, and pliability of the dragon bodies as ligatures to give even flat surfaces of paper and relief sculpture, the dimensionality and visual quality of a material knot. Perhaps then, in deliberately putting these mimetic representations of human-made knots in the bodies of these terrifying, other-worldly reptiles, it can bring the supernatural, the strange, and the wondrous, closer home.

Figure 9. The Dragon Fish, al-Tannīn, from the Wonders of Creation of Qazwini; 16th C, Bijapur; London, British Library, f. 88r.

Works Cited

Bernau, Anke. 2021. "Figuring with Knots." Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures, Volume 10, Number1, Spring 13-38.

Carboni, Stefano. 2015. The 'Wonders of Creation': a Study of the Ilkhanid 'London Qazwini'. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Gandz, Solomon. 1930. "The Knot in Hebrew Literature, or from the Knot to the Alphabet." Isis , May, 1930, Vol. 14, No. 1, May 189-214.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. 1995. The Topakapi scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture. Santa Monica: The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities.