Alumna Update: Mridula Paul

Mridula Mary Paul is a 2011 scholar. She studied Developmental Studies at the University of Oxford. Currently she works as a Senior Policy Analyst, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE). Mridula is working with Dr. Abi Vanak to raise the profile for the conservation and sustainable use of savanna grasslands in India.

India’s Savanna Grasslands: The Unsung Tale

Mridula Mary Paul & Abi Tamim Vanak

Close your eyes and think of the wilderness. What do you see? Chances are that you visualized a forest or a wooded area. While that is not incorrect, it does not present a complete picture. We live on an immensely diverse planet, with a range of environmental regimes or biomes. Biomes are distinct areas of the planet that support certain types of plants and animals based on the temperate, soil type, light and water available. Forest biomes cover a third of the Earth’s terrestrial area, but there are a number of other biomes including deserts, grasslands, freshwater, marine, and tundra. This is an important distinction to maintain, because conflating the environment with forests has dangerous consequences.

The Indian savanna grasslands are vast extents of grass-dominated landscapes, peppered with some trees, distributed across peninsular India. This biome came into existence 5 to 8 million years ago, although fossil evidence from central India date grasses back to about 60 million years. Preliminary studies point out that about 17% of India’s land mass is covered by savanna grasslands. However they are poorly understood and consequently undervalued. Grasslands were long believed to be the remains of forests degraded by humans, animals, and natural factors such as fire. These views, entrenched in popular as well as administrative memory, have implications for how grassland landscapes are managed and conserved, with impacts on the people and other lifeforms that live and depend on this biome.

Between 1880 and 2010, India lost 26 million hectares of forest land. Widely acknowledged as a crisis, there are a number of policies, programmes, and judicial pronouncements in place to combat this. During the same time, about 20 million hectares of grasslands were also lost. Somehow this never made it to the front pages. The answer to why this is the case is tangled up in history and economics. For a colonial state that was looking to generate revenue, forests were a natural goldmine. Agricultural land, although not as lucrative, still presented the state with revenues in the form of taxes. These were classified as productive lands. Grasslands, with their nomadic pastoral communities who were hard to pin down and with no obvious income generation capacity, were categorized as ‘wastelands’, a terminology that continues into contemporary times.

Colonial forest regulations treated grasslands as sub-par forests, and pushed for their conversion to tree plantations and irrigated agriculture, while outlawing grazing. This posed a threat to the vast number of species that had adapted over millennia to grasslands, as well as many pastoralist communities that had sustainably used this landscape for their livelihood. Irrigation canals built in these landscapes eventually rendered the soil saline in some areas, rendering them unsuited for agriculture. Continuing to view grasslands through its wasteland lens, independent India’s land classification norms clubbed all natural areas under the umbrella of forests, regardless of the type of biome it was. For official purposes, if it wasn’t a forest, it must be made one.

The Wasteland Atlas of India declares vast tracts of grassland area as wastelands, seemingly oblivious to its unique and rich natural heritage, and in disregard of the livelihood modes of millions of pastoralists and over 500 million of their livestock. The repercussions of classifying grasslands as forests or as wastelands is that it leaves grasslands open to large-scale diversion to other uses. When treated as a wasteland, grasslands are used as empty spaces to site commercial and development projects, and when treated as an under-achieving forest, it is dug up for afforestation or land improvement programmes, irrevocably modifying the landscape.

Extensive portions of the savanna grasslands of central India have been subjected to the construction of trenches with the use of heavy machinery, as part of watershed development programmes. Across the Deccan Plateau, grassland areas are diverted to forestry projects and bio-fuel plantations, irrigated agriculture, urban and industrial uses. Renewable energy is a more recent claim on these landscapes, with large-scale solar and wind energy infrastructure being established in grassland areas, indiscriminately cutting through grazing tracks and wildlife habitats. Over 4000 hectares of grasslands in Karnataka have been handed over to government and academic institutions to set up their campuses.

Nomadic pastoralists, with their specialized rotational grazing systems that ensure the measured use of available resources, are constrained to ever-shrinking pockets of grasslands left for their use. Ill-advised planting of trees such as Prosopis juliflora, in a bid to render grasslands more productive, have compounded the problem, as the species turned out to be an uncontrollable one that rapidly spread and encroached grassland areas. The changes to their habitat have negatively impacted grassland-specialist wildlife such as the blackbuck, Great Indian bustard, Lesser florican, and the Indian wolf. Once dominant across the range, many of these species are critically endangered, while others are on the brink of extinction.

With new research revealing the substantial potential of grasslands to sequester carbon and combat climate change, the true significance of grassland landscapes can now be conveyed using a vocabulary that policymakers respond to. Unfortunately, old prejudices still stand in the way of this understanding translating to political action. Global programmes that aim to reverse land degradation, such as the ambitious Bonn Challenge, are largely tree-plantation drives. During a recent meeting of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in September 2019, the Indian Prime Minister declared that 26 million hectares of degraded land would be restored by means of additional tree cover by 2030. This is also in tune with India’s climate commitments under the Paris Agreement to create an additional carbon sink of about 3 billion metric tonnes.

Plans to increase forest cover are met with resounding cheers. Where exactly these trees are being planted however, tends to slip from focus. Clarity is missing on what exactly counts as degraded land, and whether non-forested, but highly ecologically rich landscapes such as grasslands are being misguidedly coopted as potential afforestation sites. While forests are undoubtedly great carbon sinks, grasslands are not all that far behind. Studies reveal that restoring grasslands is an immensely effective and economical way to combat climate change, as these landscapes store large amounts of carbon below ground. When a nuanced and informed understanding of the importance of grasslands filters into conservation and climate change policies, it will be win-win for pastoralists, grassland biodiversity, and the planet. Until then, the survival of India’s savanna grasslands hangs by a blade of grass.

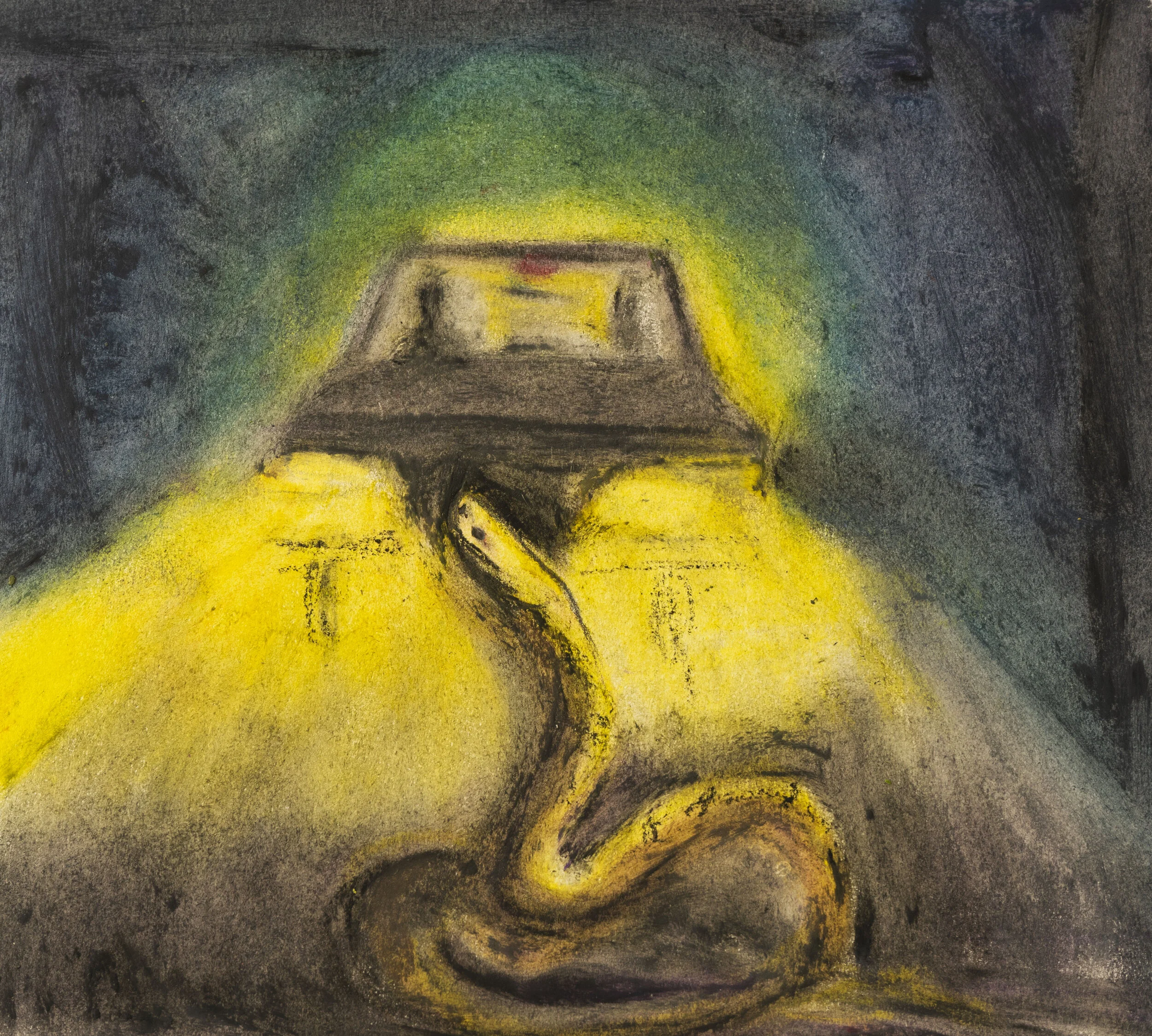

Image credit: Dr. Abi Vanak

Dr Abi Tamim Vanak, Senior Fellow (Associate Prof) and Convenor, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE)