Inlaks Research and Travel Grantees 2018: Geeta Thatra and Vishal Singh Deo

Geeta Thatra and Vishal Singh Deo are the 2018 Inlaks Research and Travel Grantees. Their interests lie in personal and collective memories. Geeta’s research is motivated by her her family’s experiences of partition while Vishal’s urgency is ignited by a passion for history and how certain events have shaped the world we live in today.

Geeta Thatra

Last year, we marked 70 years of Partition of the Indian subcontinent. The diverse events commemorating one of the cataclysmic events of the twentieth century explored the trauma and turmoil of the partition, individual experiences or family histories of the survivors, memories of belonging, and the modes of archiving such partition stories. It was a significant moment that decentred the ‘moment of arrival’ and attempted to reflect upon the entwined history of independence and partition.

With my grandmother on a family visit in November 2013, two years before she passed away

My journey into the field of Partition Studies did not begin as an academic exercise. I grew up listening to my grandmother’s stories of migration from Shikarpur (in Sind) to Bombay, and eventually to Bangalore. The names, dates, and episodes of ‘high politics’ were elusive. Her recollections were not so much of partition as a historical event but of the family’s flight to make ends meet. Having accepted the fate of labouring in her life, my grandma narrated her several entrepreneurial forays to secure our living. She interlaced these tales with details of urban life like watching first-day-first-show movies, taking off on day-trips to Savandurga or playing teen-patti with her friends that arose in me much awe for her.

Growing up in Bangalore, and my higher education in Bombay and Calcutta, very often provoked questions about my family’s history and the unusual surname that I inherit. I accompanied my grandma a few times to Ulhasnagar (a thriving township of Sindhi ‘refugees’ located 50 kilometres from Bombay) to familiarise myself with our extended family and her business. Although it was a sheer pleasure to listen to Sindhi spoken all around me, and savour the quintessential Sindhi delicacies like dal-pakwaan, chola-chaap, batan-papdi, rabdi-falooda on the road-side, I felt too distant and disconnected. The class-difference amongst my relatives in Bombay city and Ulhasnagar was striking, and so was the disparity within the community.

In my extended family or community gatherings, we never spoke about the partition or expressed nostalgia for Sind. It was a strange kind of silence. We were not told of what happened, but we were warned from getting too friendly with Muslims lest we desired to marry them. Such restrictions did not sit too well with me, especially when I observed inter-mingling in the spaces of business. Surprisingly, these concerns were not echoed by the first generation of partition ‘migrants’ but by the second generation. I lived with these thoughts, discomforts, and unfamiliarity until the questions of ‘insider/outsider’ in my previous research pushed me to explore ‘my’ community’s past.

My previous MPhil research explored the caste-based spatial organisation of Bombay and the production of a segregated Dalit neighbourhood. Before this, I worked on the performance spaces of tawaifs, incidentally located opposite to Congress House (the nationalist hub of Bombay). I also explored the lives of women bar workers from Bedia, Deredar and Kanjar communities in the aftermath of the ban on bar dancing. These studies were about marginal communities and spaces of Bombay and conducted amidst the rising tide of questions about the politics of representation and knowledge production by the anti-caste movement. The challenge for me was to direct a more critical gaze inwards, and that’s when I turned my attention to writings, films and scholarly literature on the partition, and embarked on my research.

My PhD—City, Community, Partition: Sindhis and the Making of Bombay in the Twentieth Century—explores the reconfiguration of Bombay at the time of partition. Bombay is not immediately associated with the partition as it was not divided by Radcliffe’s boundary line. It was at a distance from the carnage that occurred in 1947, yet affected by partition-related violence and chaos, influx and flight. My dissertation pursues a recent trend in Partition Studies—that shifts its gaze from the ‘high politics’ examining the genesis of partition on the one hand, and the multiple ‘meanings’ of the event on the other—to explore partition’s impact on the spatial reordering and social relations of Bombay. Probing the politics of rehabilitation policies and juridical processes, I explore the making of salient categories including ‘refugees’ and ‘evacuees’. My underlying premise is that Bombay is not merely a site to understand the meta-processes of partition, but how the city and its communities were constituted through these very processes. Such questions have gained salience amidst the renewed debates on citizenship and enemy property in India, and the insecurity of minorities and refugee crises the world over.

Chandra (my grandma) is second from the left with her four sisters who lived in Ulhasnagar, and a sister-in-law from Bhiwandi. All these women headed their households

Going to the UK for archival work is crucial for scholars working on the partition and its displaced communities due to the challenges of working with fragmentary archives and limitations of conducting cross-border research. The British Library and The National Archives hold rich corpus of materials like the All India Muslim League Papers, Jinnah Papers, Partition Papers, and the private papers of British officials, which are critical for understanding the contentious and protracted negotiations between India and Pakistan regarding migration, displacement, and rehabilitation. I am thankful to Inlaks Shivdasani Foundation for awarding me the travel grant to pursue research in the UK.

Vishal Singh Deo

My journey in to academia and interest in caste history and politics followed a rather unconventional path. My family settled in Hyderabad after my father retired from the army in 1996. Back then my only form of recreation was to be out in parks and grounds, mimicking cricketers with the hope of representing the country someday. Cricketers in Hyderabad were selected by means of an average academic record, compensated by evening tuitions. My circumstances were no different. After my schooling I enrolled as a commerce student only because I wanted to continue playing cricket. As I grew out of college my interest in the game finally succumbed to the pressures to earn a living. Therefore, I took up a job as an insurance salesman.

My work introduced me to hundreds of prospective clients each month. Some who would go on to become friends, while some who would offer a blank stare. After a few years I decided it was time to move onto something I felt strongly about. My generation had grown up during the years of the Babri Masjid demolition and much later, the 2002 pogrom in Gujarat. Much of my spare time at the sales job was spent reading history, especially books about caste, identity and communal strife. I quit my job in 2010 and in 2011 was enrolled myself in the department of History, University of Delhi as a Master’s students.

Through my Master’s program, followed by my M.Phil, and research projects with the Rupayan Sansthan in Jodhpur I was able to sift through the nuances in caste and community. My scholarly engagement rested on a desire to engage with the local economy and ecology to understand the processes that shaped formal and informal political representation in colonial north India. For instance restrictions on grazing and cultivation rights in the 1880s represented a major shift from pastoral spaces to a more aggressive and sedentary style of agriculture. Importantly, it unpacked the positions adopted by caste individuals in the 1910s in Gau Rakshani Sabhas and the provincial legislative council in demanding a ban on cow slaughter.

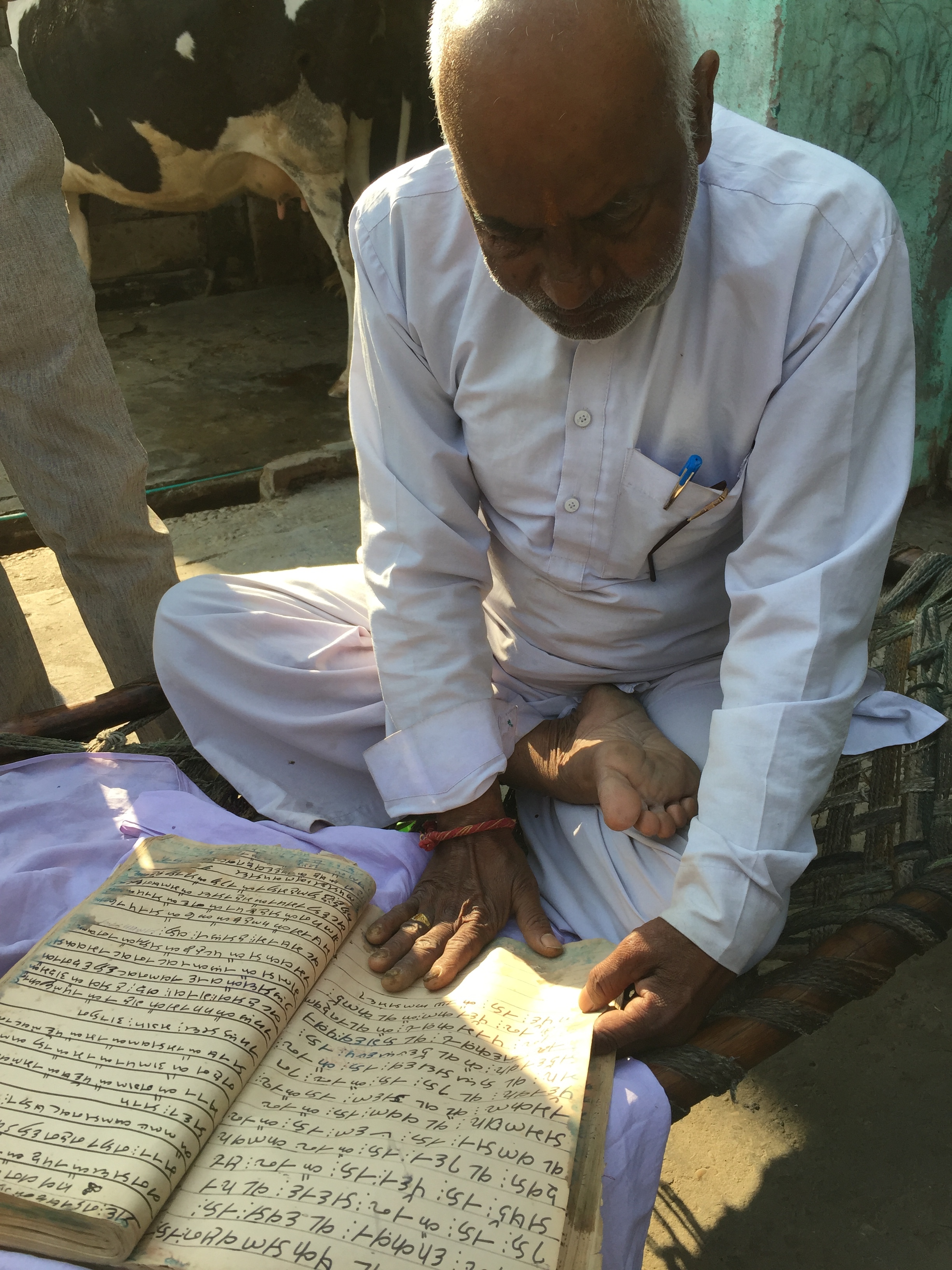

In 2017 I moved to Muzaffarnagar to ground myself more firmly in the region. My thesis was troubled by the noise of the many native terms used by the revenue officers while compiling their reports. These terms written in italics appear to carry great weight in the region and remain an essential part of our oral memory. Local caste genealogists or bhats would nonchalantly make strong references to narratives that appeared as stray references in the colonial accounts. Such pieces of evidence allowed me to revisit the understanding of colonial land grants. If oral memory could guide me to understand land rights it also led me to unearthing documents that betrayed the colonial position in bracketing lower castes within a category known as the ‘professional caste occupations’. Evidence of dominant castes capturing land from the lower castes can be found in the dusty record rooms of Muzaffarnagar district administration.

During this time I also began volunteering with the Afkar India Foundation, a not for profit located in Shamli- Muzaffarnagar. The organisation was and continues to remain involved in the relief and rehabilitation of riot victims, affected by the violence of 2013. More recently, we have started working on the issue of Dalits and landlessness towards a probable unionisation of informally placed agrarian labour. Work is also underway to build an oral and written archive documenting land dispossession, extra-judicial killings and hate crimes.

My doctoral work has so far profited from the available documents in Delhi, Muzaffarnagar and Lucknow. Yet there remain essential gaps due to the paucity of necessary documents that I have traced to the catalogue of the British Library. For more than a year now I have listed down relevant references of private papers, manuscripts, intelligence reports and personal memoirs located in London. I therefore have none other to thank than the Inlaks Foundation for offering me this grant. The opportunity to devote up to three months researching and writing at one of London’s finest research facilities is a prospect I very much look forward to.